Blessings and Curses; Blessings (2022)

Solo exhibition at Dvir Gallery, Tel Aviv

“Blessings” is the first chapter (as the name suggests) of a larger exhibition. It deals with two distinctly marked spaces: East and West. In both its parts, it speaks in a polyphonic voice: it surrenders itself and oozes affection – while at the same time insulting the intimate immediacy of the “act of painting”, shredding its individuality and originality. In both spaces it is an innocent, elaborate, and playful painting technique; on the “west”, oil paintings were photographed, processed via Photoshop, and printed on canvas which was painted again in gouache. On the “east”, computerized collages inspired by greeting cards were processed digitally, printed on canvas, and painted in oil paints.

The exhibition’s action is twofold. On the one hand, surrendering to the “root of good” (the “pure intention”, free from conflict, which characterizes the gesture of blessing, and also the vibrating, Kabbalistic, harmonious and ecstatic foundation of prayer). On the other hand, constantly, actively, and feverishly exposing the inherent inability of the blessing and the prayer to be seen in their innocence; externalizing their self-extradition into the space of labeling and coding.

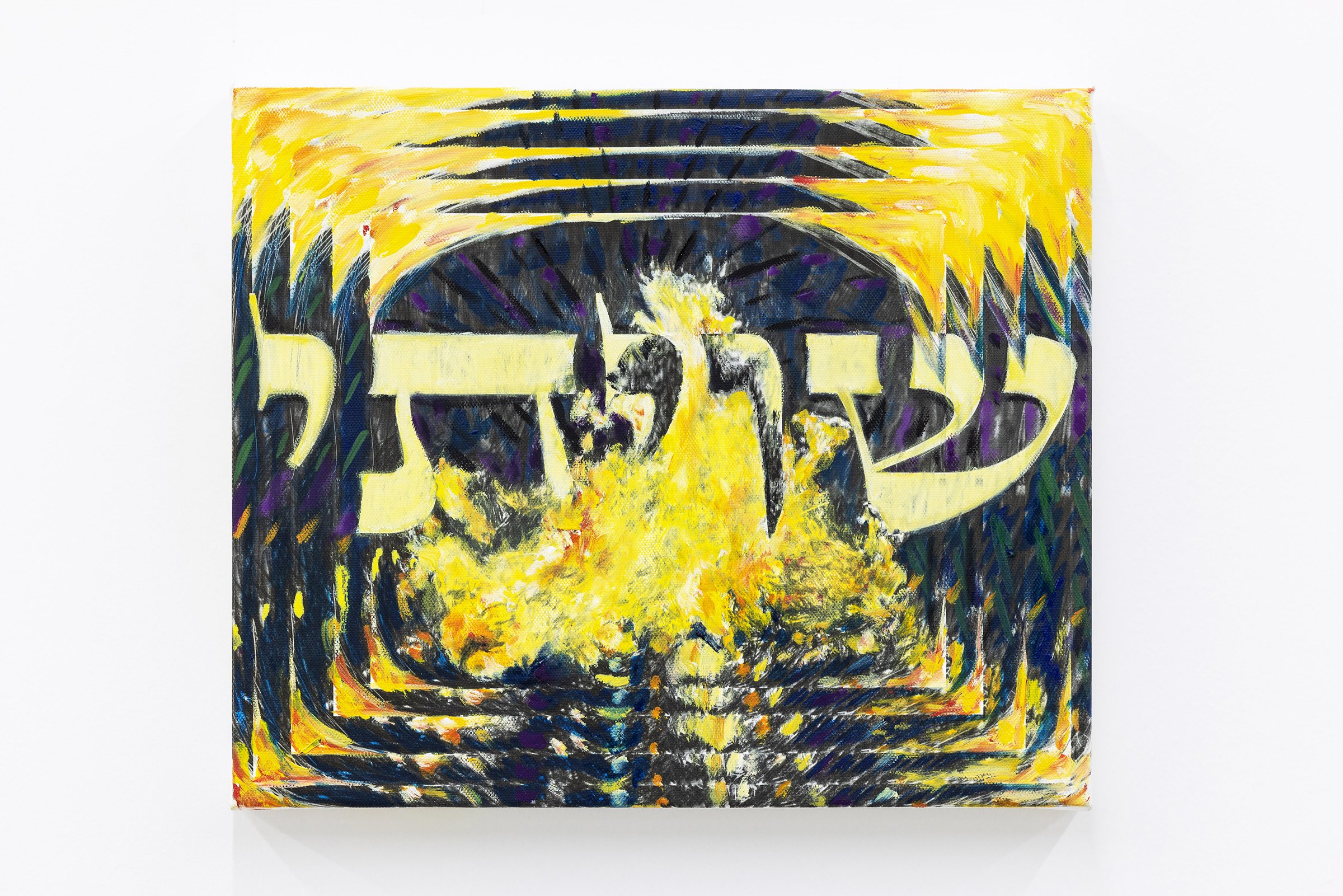

The exhibition is twofold in its use of space, also. It is arranged as a bow tie. The western wing of the bow tie contains mainly images that relate to the Jewish, Kabbalistic, and mystical act of prayer, the organs of prayer, the garments of prayer, the movement of prayer, and its moments of ascension. This is the “painted” part of the exhibition, most of which pay tribute to Jewish painters from the late 19th and 20th centuries among others. In it, Fatal uses ordinary pictorial elements (abstractions, color surfaces, fluidity, dots, sharp drawing lines) in an extravagantly generous and borderline-incidental manner, while at the same time winking at stenciled tarot images and the posters of rebellious youths.

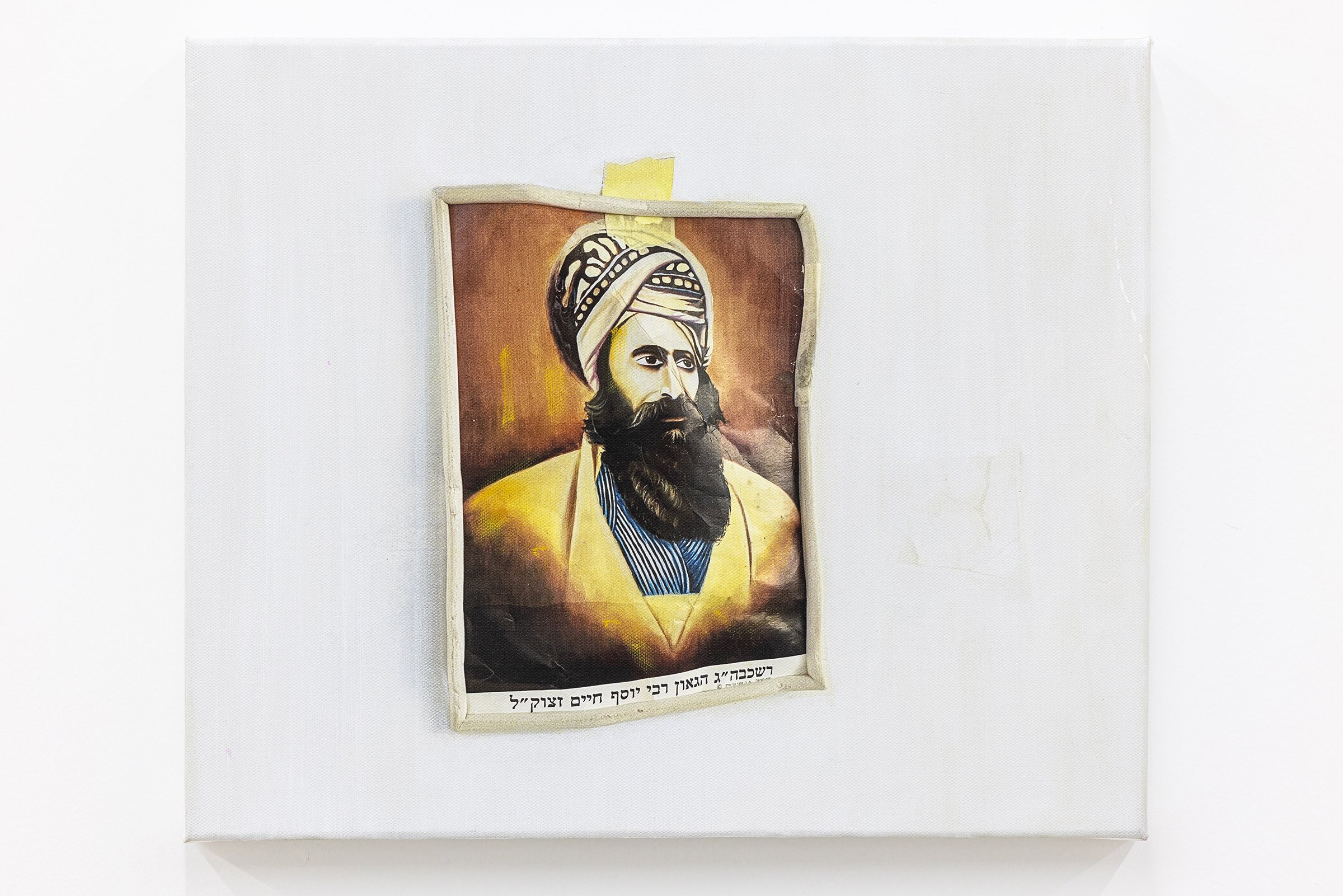

The other part of the bow tie – its eastern-Israeli-Zionist side – is a tribute to generic greeting cards that were common in Israel in the 70s and 80s. Fatal attributes to the greetings a gluttonous, playful treatment, while willingly responding to their vulgar, nationalistic, and patriotic dimension.

Fatal’s brushstrokes on the printed canvases are a reversal of the expected: the paintings of the western wing are overpainted with gouache, the disembodied brother of oil paint, a kind of nod to one of the canonical symbols of Israeli painting. The paintings of the eastern wing of the bow tie were treated with the callousness of oil paint, the “high” and demanding material associated with classical Western masterpieces, signifying now the glossy kitsch richness of commercial blessings.

The paintings are charged with homages – simultaneously innocent and playful – to painters, to styles, to the artistic and commercial, to high and low. The “eastern” wing is characterized by confusion and noise – the same noise that is an inherent part of the “eastern” image, which is viewed as stereotypical, popular, politically-oppositional, and above all aesthetically cheap and abundant. Another abundance, spectacular and ironic, emanates from the western wing of the bow tie: an abundance of the sublime.

The two sides of the bow tie are soaked with both deep closeness and discomfort, from which the question arises: where is the painter’s home? On which side of the bow tie, east or west? A blessing or a prayer? And the answer is obvious: it’s in both. But both are disturbed homes, in which it is impossible to live “naturally”, to actually dwell. However, it is doubtful whether Fatal actually lives, as one is led to think, in both. It is better to say: he moves between the two, claims both homes for himself, expelled and exiled.

“Blessing” is an almost crude, simple thematic arrangement – which maintains within itself countless affinities, connections and reverberations. Seen from a distance, it seduces the viewer with material and colorful richness. A closer look will reveal, as mentioned, the art of reproduction, the computerized treatment, the false canvas layers. The canvas – the distinctive sign of western painting, of its values and artistic summits – is the foundation of all the works in the exhibition, but Fatal’s complex technique turns its use into a pretense (“It’s a painting!”), and at the same time a reference to the popular commercial use of canvas, which has been usurped from its purpose as a medium for ‘real’ painting. A long-agreed forgery is no longer a forgery. The canvas beats the painting; the painting is forgotten, and the canvas is a relic standing on its own, an empty, unapologetic, unembarrassed signifier of prestige. The core question of Fatal’s exhibition is the platform; the canvas, instead of being the first layer, becomes almost the last. The only constant element in a painting (the canvas) becomes interchangeable and serial. The computer, with the multitude of manipulations it allows, is not only a medium, but also a substrate for itself. If we think of the platform as identity, it seems that Fatal converts this main point from knowledge to a question, from certainty to doubt, from source to betrayal.